Preparing your order

This article was originally published in Wired UK, which has since undergone a site redesign stripping out all the videos and imagery, rendering a great deal of it baffling. An older, partially-restored version is archived here and a director’s cut web-designed version below for posterity. It was written in May of 2020, deep in the trenches of the (then novel) COVID-19, by way of context.

A Faustian bargain is currently being entertained in WhatsApp groups across the country, growing in appeal by the day. What would you give to escape the lockdown for a single stolen hour, to share one pint with your pals in your favourite pub, right now?

There have been a lot of valiant attempts to circumvent our coronavirus restrictions, with people ‘sharing’ virtual pints with the aid of Zoom, but I can’t help but feel like there’s something fundamentally lacking. Sure, I can see my friends, hear their half-baked exit strategies; laugh along at their inscrutable patter; nod sagely at their garbled soliloquies on all things life, love and art, and I’m also undeniably still pissed out of my tiny mind, but it’s just not the same.

The space where this experience takes place is a crucial part of the experience itself. Without it, I’m just getting battered on my own in a room I wish I wasn’t confined to. But what if there was a way to bypass all of this? What if there was a way to bring the pub into my living room without having to smash a hole in the wall? What if I could bring my nearest and dearest to me, without them having to break lockdown? What if I could transcend the limitations of the physical world? What if I could make my local pub in VR?

***

It is fair to say that virtual reality hasn’t taken off in the same way as, for instance, the lightbulb, the television, the phone, the internet and the washing machine. What should have been the final frontier for home entertainment hasn’t – yet – broken beyond being a preserve of the niche enthusiast.

“The asociality of VR is a big factor,” says Rob Morgan. He’s the founder of Playlines, an augmented reality company combining digital media with location-based live performance (“it’s a bit like Pokémon Go meets Punchdrunk Theatre”) and has been a scriptwriter on a number of VR projects, including The Unfinished (which screened at Tribeca in 2018) and 2019’s VR Game Of The Year award winner A Fisherman’s Tale. “It creates a really high level of demand on a player’s time and their engagement,” he says. “It’s turning your phone off to watch a film in the cinema, as opposed to watching on a television.”

But, for the most part, VR developers haven’t dedicated a great deal of time to rendering the more banal locales up until this point, most likely because your average player can just visit them in real life without splashing out on hundreds of pounds of technology. Or at least they could, until lockdown hit.

As a man of very little – or perhaps, too much – taste, I would make my living room look like a pub, if only I could. But unfortunately I do not own my own home, and even if I were somehow able to convince my landlord to allow me to embark on a lengthy and ultimately market value-deflating renovation of their living room, it is unlikely that the relevant authorities would consider my bootleg bar-building essential construction work right now.

But I do have a laptop*, an endless supply of YouTube tutorials, and a lot of spare time. (*It became immediately apparent that my own laptop’s capacity to handle any sort of CGI was fatally compromised, but Cassette generously lent me one that didn’t try and self-immolate whenever I asked it to do anything more advanced than display screenshots from the original Toy Story on Google.)

“In the next few months, we will see a Golden Age of people making homebrew games,” Morgan predicts, especially for VR. This is encouraging, particularly given the almost literal nature of my own homebrew attempts. What is less encouraging, however, is his matter-of-fact assessment of the skills and time required to make a pub in VR. You would, he says, normally need four people for a project like this: someone on design and environment, someone on animation, someone on sound and someone to package it all up. “A decent three months, and it’ll be good. If you don’t mind a bumpy experience; two months and it’ll be fun,” he says. I am one person, with zero experience in any of the necessary fields, who has already told WIRED I will try to deliver something within the next few weeks.

“It’s a humbling experience, trying to make games,” Victor Brodin tells me over an animated video chat. As well as being a self-taught VR developer in his own right, Brodin is a community manager at Epic Games, whose Unreal Engine 4 (UE4) – the bricks and mortar of the video game industry – I will be using to construct my pub.

“If you can make a box feel nice to sit in, with lighting, then you’re off to a good start,” Brodin tells me, but there’s a lot more to think about. “Research. Lights, cinematics, how you blend colours to feel inviting, what materials the human brain finds interesting. I would start there: If I was an interior designer, how would I make this space comfortable?”

Brodin has worked on numerous VR experiences, including Perilous Orbit’s Social Club VR, an online multiplayer which drops you in a high-class casino and lets you chew virtual cigars over games of blackjack and roulette. During production, the team would have meetings within their VR environment, both to gauge how well they’d pulled it off and what they’d need to improve, but also because they were working remotely. VR was able to provide them with a physical office space that they could commute to without leaving their homes. “Video games are an illusion. If you’re able to capture the player in your illusion, then you’ve done a good job,” says Brodin. “It’s exciting. You’re playing God, in a way. You’re doing new things, which you can’t say for many other mediums.”

Theoretically, UE4 gives you the power to craft any world your imagination can conceivably muster. You could devote yourself to amassing enough knowledge of architecture, interior design, anthropology, sociology, mixology, aesthetics, brewing and general publican lore that you could produce a blueprint for the objectively perfect pub.

Thankfully, I don’t need to, because it already exists.

Skehan’s – on the corner of Kitto Road and Gellatly Road in Nunhead – is the best pub in London, arguably in Britain. Why? Because it is my favourite pub.

It started life as a coach house, around 200 years ago. Carriages bound for France would arrive here, and their riders would rest their horses and refuel their spirits in the downstairs saloon bar, before retiring to the rooms upstairs ahead of catching the ferry the following day.

It spent the next two centuries being passed between Irish families, up until 15 years ago, when the pub formerly known as McConnell’s was passed onto Bill Skehan, who gave it its current alias. By now, the horse’s quarters had become a beer garden, and the stables were turned into Chai’s Garden, a Thai restaurant run by and named after Bill’s wife. Five years ago, Bill’s nephew Bryan Fitzsimons became the latest owner – though Bill’s family still live on the second floor, with Bryan’s on the top.

“I think it’s important that the family are in the pub,” Bryan stresses to me over the phone. “That’s what makes it. You walk into a brewery, or a chain, and they don’t live there, do you know what I mean? This is our home, there’s always one of us around somewhere.”

The various families who have acted as custodians of the building now known as Skehan’s have taken care to preserve its Victorian-era origins. Having a personal stake in a bar as a living space is probably a useful curative to any entrepreneurial demons on the shoulder, whispering for you to rip out all the original fittings, expose the brickwork and daub the walls in kitsch monstrosity or sterile modernity.

The interior decor would’ve once been considered ubiquitous – perhaps unremarkable – pub fare, but has since been rendered something of an endangered species. Crimson red walls matching the upholstery of the banquettes, fern green suede bar stools, mahogany wall panelling, cast-iron fireplace, brass fittings along the bar, etched glass mirror, Guinness-sodden antique furniture, all sorts of accumulated knick-knackery and framed portraits of anonymous pissheads.

There are also several television screens (ideally placed for weeknight Champions League games, but unobtrusive enough when the occasion is of no interest), you can get dinner in the bar every night, and there’s a piano. And music. Always music. Skehan’s is simply superior to all other pubs. It’s the pub I want to drink in most, and it’s therefore the pub I’m making in VR.

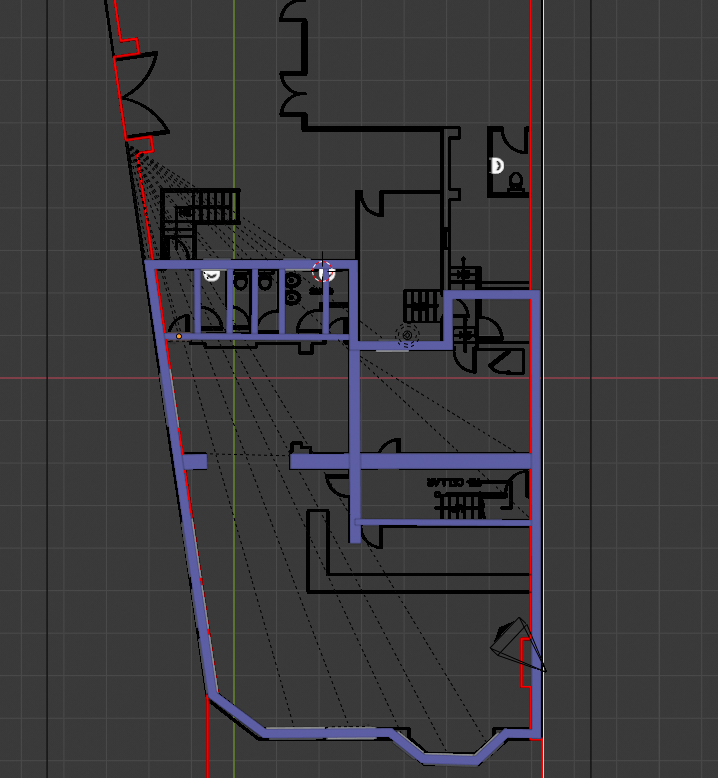

Bryan was kind enough to dig out the blueprints for the bar and send me some reference photography, so I downloaded Archipack, an add-on for the open-source 3D software Blender, and got to work creating the base structure.

Learning 3D, from my experience, seems to be a process of discovering that things you assumed would be bafflingly difficult are surprisingly easy, and vice versa, and I’d assumed that this would be the most difficult part. To the architecturally ignorant, buildings are often very large, and take professional construction workers ages to put up. Months. Years, even. My clueless logic followed therefore, that large equals difficult.

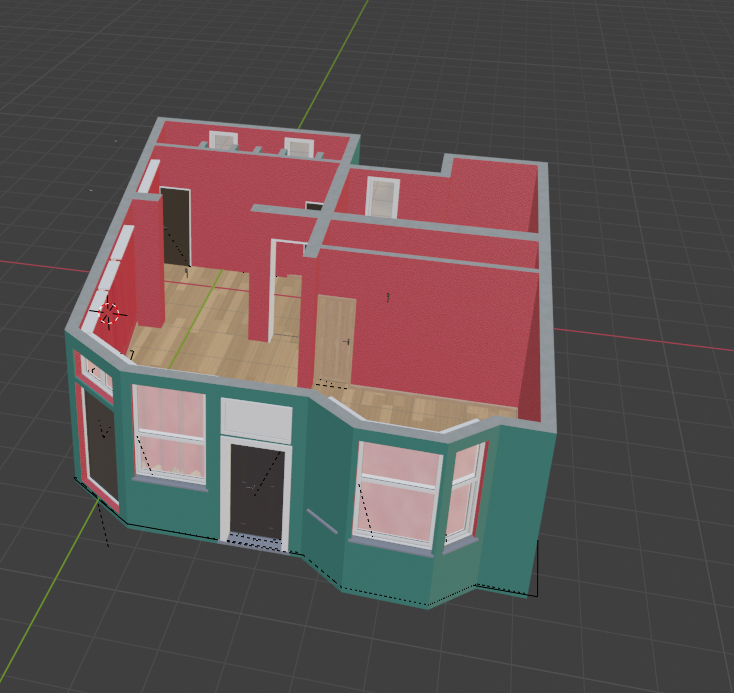

Within the space of an afternoon, I’d made a room with the dimensions of Skehan’s, replete with doors and windows. It looked like Skehan’s. Well, enough to be recognised as Skehan’s by the people I excitedly sent screenshots to. At this point, I got immediately wildly carried away with my newfound capabilities, predicting I’d be able to get the small matter of window dressing done in no time.

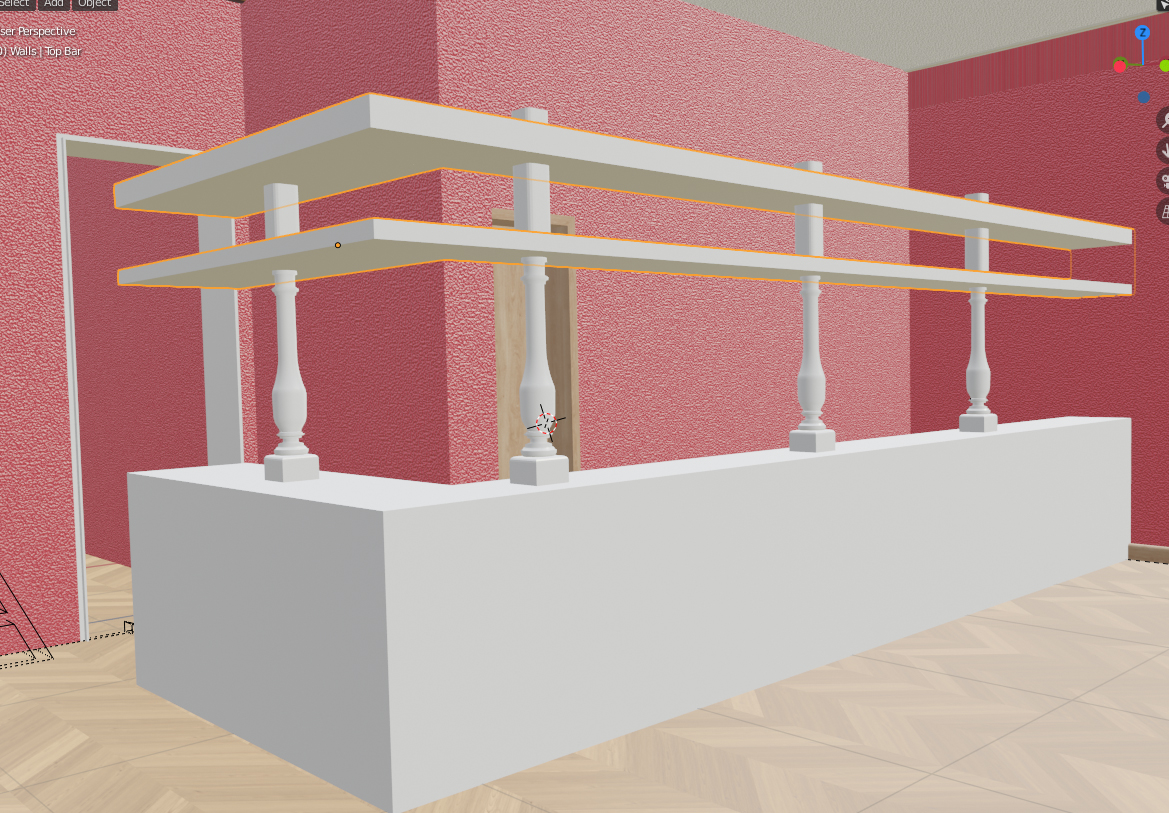

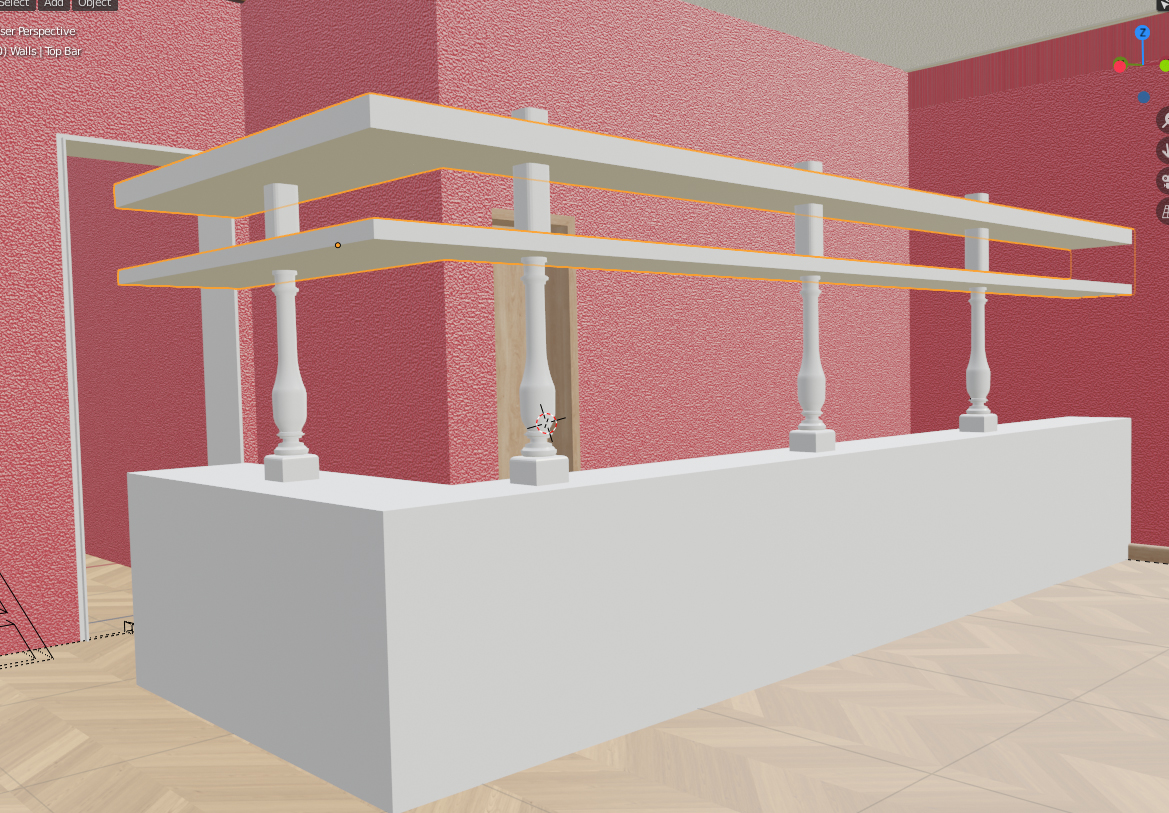

Window dressing takes ages. After a gruelling bout of wrestling with Blender, I manage to replicate near enough the exact shape of the banisters holding up the real bar, for reasons that seemed to make perfect sense while I was in the process, but no sense at all when I realise that it had taken me an entire day, and that you are probably not reading this hoping I really nail the accuracy of the virtual banisters of a bar you’ve likely never been to. I make the same mistake trying to get the dormer roofs and awnings outside bang on, only remembering – two days in – that the purpose of the exercise isn’t to have a drink in front of the pub, but inside.

Though I am slowly gaining a rudimentary understanding of 3D modelling, I follow Brodin’s advice and bin off attempting to meticulously recreate the exact curvature of the table legs and the majority of the other assorted trappings inside in favour of scouring the various asset packs available on the Unreal marketplace and modifying them until they look enough like the thing they are supposed to represent.

Then it comes to texturing the thing so that it doesn’t look like it’s made of LEGO. I repeat the above mistake, diving headfirst into a new program – Substance Painter – in some unconscious Sisyphean attempt to prolong the whole process.

“What are you doing now?” asks my girlfriend.

“I’m trying to replicate the exact grain of each of Skehan’s floorboards,” I reply.

“Why?” she asks, and I have no answer, now very aware of how the exercise appears ‘very alarming’ to anyone else. I follow Brodin’s advice once more, and make use of Quixel’s Megascans library – an enormous resource of textures scanned from real materials and objects, free for use with UE4 – for the rest.

This works to varying degrees, as it transpires I didn’t ‘unwrap’ a couple of my ‘UVs’ properly before exporting them from Blender, which results in parts of the structure looking like a Dali painting across a deflated balloon. However, I’m able to use the red stucco wallpaper material I created in Substance Painter on the walls, which everyone, including and especially you, is really impressed by.

Once you get sucked deep down the rabbithole of trying to replicate something within VR experience, you gain an appreciation for how much of your experience of reality has been consciously curated, and isn’t just random happenstance. Lighting, for instance. If you walk into a pub and you’re met by punishing fluorescent white, you will likely walk straight out again, not wanting to spend an evening losing sobriety in something that feels like an open plan office.

Aside from the functional spotlights lining the top of the bar, which allow staff the useful benefit of being able to see what they’re serving, Skehan’s has a number of light fixtures, chandeliers and the like, which are largely just for show. “We try and keep the soft lighting in there,” Bryan says. On winter evenings, the pub is lit almost entirely by candlelight and the crackle of the logs burning in the fireplace.

The light fixtures disguise the deceptively high ceilings, and it’s only when it comes to lighting the room that I notice how intricately ornate the real versions are, something I’d been oblivious to while drinking beneath them, and also while I was modelling the thing, so my replica is just a blank slab. It’s also a surprise to me to learn that the ceilings are white, given the cosy darkness I associate with the place.

White is the most reflective colour, and playing around with my attempts at candlelight and various roughness values (which, crudely, dictate how much light is absorbed by a material) of my wall, floor and ceiling textures, I realise what a frustratingly delicate dance it is trying to stop your space looking like a garish child’s doodle of a pub, or a dingy sex dungeon. Eventually, I manage something which straddles an acceptable medium between ‘rejected Harry Potter N64 game-of-the-film’ and ‘visible’.

To round up the rest of the build:

– To skirt around a tedious process of sourcing the original artworks adorning the walls, I simply replaced all the framed pictures inside with pictures sourced from the ‘good pics’ folder on my desktop (mostly of my pals, and also of Arsene Wenger.)

– I discovered there’s a significantly easier way of adding plants only after painstakingly jigging about various models to replicate the greenery that runs up the sides of the building and engulfs the garden. They don’t look anywhere near as resplendent as Skehan’s, but it was important to get them in, as they’re a big part of the pub’s aesthetic – having morphed from a means to hide graffiti into a statement feature.

– Either the floorplan Bryan provided me with was wrong, or, more likely, I made some sort of fatal error, because my toilets were an absolute disgrace. Skehan’s actual loos are perfectly fine, and crucially, usable, but spending any time entombed within my pixel bogs, and you’d come away severely traumatised by small spaces. I briefly thought that maybe the scale would make more sense if I placed a toilet model within them, but then concluded it would be physically impossible to enter mine without smashing the door into the guy standing at the urinal, shattering his spinal column.

With the interior and the exterior of the pub, I set my sights to the far more straightforward task of adding a pint. “The action of grabbing something in a virtual world, that can be the thing that needs to feel the best,” Brodin points out. “You might not think it, but sometimes, it needs to be the thing – I can hold the beer bottle, it feels so good.”

This takes me several days.

After watching about 50 tutorials at x2 speed and failing to make any headway, and briefly considering falsifying footage of my own hands holding a beer in front of a green screen, I eventually manage to fashion a lurid-looking substance using a shader from the Unreal Marketplace which moves according to the tilt of the glass. It might look like my luminescent lager will irradiate your internal organs faster than a failed nuclear reactor, but unless you want to create me a fully functioning pint system, which I’d be eternally grateful for, keep your damn criticisms to yourself.

After two-and-a-half weeks of shredded nerves, innumerable basic errors and about three nights’ of actual sleep, I am finally ready to ‘enter’ my pub. HTC kindly lends me a Vive Cosmos headset to test it out, and I audibly gasp when it doesn’t result in a great big error message and an exploded laptop. The whole thing is actually… surprisingly convincing. Technology is amazing. I take the helmet off, and quietly announce to my girlfriend. “I did it, I made Skehan’s.” She puts the helmet on and promptly tries to put her fist through the wall, to test the environment. “Very good,” she says, and then goes about the rest of her day.

I plonk my character down in my favourite seat in the pub, and drink my incandescent pint. And lifting that pint using the inputs mapped to the Vive motion controllers… it feels good!

Carried away by the possibilities of the technology once more, I organise a Zoom call with Ultraleap’s Tom Carter, who tells me about the potential of the STRATOS haptics range. Ultrasound waves can be programmed so a player would ‘feel’, for instance, a stream of draught beer being poured, or the airblades in the gents, or even a pint glass (though Carter points out that ‘feeling’ the virtual glass doesn’t stop you physically putting your hands through it.)

I get big ideas about making a working, ‘feelable’ dart board, pool table, beer tap, jukebox, quiz machine, karaoke system, working TVs, books and newspapers you can actually read… I want total immersion. Then I put the Cosmos back on, get back to my spot and start happily supping at my virtual pint and irl pint again (a somewhat difficult physical process while wearing the headset, but nevertheless an essential one for Total Immersion).

‘I did it, I made Skehan’s…’, I keep thinking to myself. “I did it…”

But something doesn’t feel right. I haven’t made Skehan’s. I’ve made an empty room that looks like Skehan’s. It’s not the same.

Rob Morgan thinks he knows why. “VR sets up an extremely high standard of realism and makes big promises about our level of involvement in the action it presents,” he explains. “But if the emotional scenario in the sim isn’t engaging, if there aren’t any emotions at stake, if the fact that we are really there doesn’t actually matter, then it doesn’t matter how much money you’ve spent on the visuals. Users can immediately verify that the scene isn’t real.”

If drinking on your own in your own living room doesn’t feel like a pub, does drinking on your own in someone else’s (namely, Bryan’s) living room – which very well may technically be a pub – feel like a pub? Not even Bryan thinks so, and he can walk downstairs and drink in the real, physical thing, anytime he likes. “To be honest, it’s not much better than sitting in anyone’s house, because there’s nobody there,” he says. “It’s the people that you miss. It’s a big family. So you’re missing a lot of friends. The staff. The neighbours. The people who drink in here.”

“A pub with no people in it is just a mausoleum for yeast,” agrees Morgan. “For me, a virtual pub should be an authentically social experience.” My virtual pub doesn’t feel like a real pub because my pals aren’t here. It’s not the drinking or the space that I miss, it’s the prospect of spending an evening and an unjustifiable amount of money just to blabber increasingly incoherent inanities in the company of the people I love. It’s slapping my card down and conspiratorially promising one more, even when it’s no longer my round, even when I don’t need another and even though my head is already making plans to regret this in the morning, if that’s what it takes to extend our time together and to stave off the respective daily grinds that await us, before we have to slope off into the night. And then one more after that.

I begin to wonder if I’ve spent weeks isolated even within self-isolation, soldiering away on a solitary task to prove to myself that I miss my friends, whom I’ve been ignoring to make my pub? Do I even like the pub? Or do I just really like my friends? Why am I so fond of pubs, and so particular about them? And why am I not content with video chats and phone calls? Is it the confluence of the two – pub and pals – I’m craving?

I need to put my pals in my pub.

If it isn’t already painfully obvious, the third dimension is not my forte. I can now make an inanimate building, sure, but people? That move? Within a couple of weeks before the deadline for this piece is due? To a reasonable degree of fidelity that you might momentarily be convinced they were actually in a pub with you? Slightly more difficult.

Over the previous few months, I had picked up some hobbyist experience by attempting a CGI render of my housemate, Andy Barr, but found I always fell short when it came to fidelity. My insistence that it was “not yet possible to render a head as small as his” did not stand up to much scrutiny, either of existing technology, nor of his head, which – upon further study during the 3D-modelling process – is not actually freakishly small at all, as I’ve long maintained. I needed to take this to the next level.

I enlist the help of Reallusion, a developer which provides a suite of character animation software used both within the industry, and by people like me, who would be otherwise limited by their budgets, bedrooms and technical knowledge.

I diligently set about getting people I know to send me passport-style photos of their face and feeding them into Reallusion’s Character Creator 3’s ‘Headshot’ plugin. Within a few clicks, you can get something which is, exhilaratingly, a pretty discernible likeness of them. Given the capacity for those with more patience and talent to export these base models into other programs like ZBrush for further sculpting, or else adjust the vast array of morphs built into the plugin, Headshot is an exciting proposition for anyone looking to create near-realistic, fully-rigged characters in very little time, cutting out all manner of previously essential intermediary processes.

It occurred to me here that, as well as people I actually know, I can also add anyone I’ve ever wanted to go for a pint with whose picture exists on the internet.

Now I need to make them move. “A NPC [Non Playable Character] in motion is always less uncanny than a NPC standing still,” says Morgan, which is encouraging, because it’s easy enough to export them from Character Creator into iClone, Reallusion’s animation software, give them some arbitrary walk motions, and then send those into UE4 in real-time with the ‘Live Link’ plugin. Less encouraging, however, is Morgan’s sage further advice. “NPCs in VR give the user an instant and unforgiving yardstick for realism, because our social senses are even more finely-tuned than our physical senses.”

It is feasibly possible to create semi-realistic NPCs of my friends entirely using the animation tools within iClone given time, but time is not a quantity I have. I’m gasping for a virtual pint asap, and therefore need another solution.

Xsens and Rokoko agree to send me their motion capture suits, the MVN Link and Smartsuit Pro respectively. The MVN Link is a several-industry-standard lycra number requiring a fairly demanding amount of set-up and calibration. The Smartsuit is an out-the-box jumpsuit, capable of less accurate capture than a properly-calibrated MVN Link but retailing at around £2,500, it’s around five times cheaper. Both can be streamed through iClone’s ‘Motion Live’ plugin, into UE4. Both are far beyond the requirements of a depraved quarantine-addled attempt to bring one idiot’s memory of the pub to life. To emphasise that point, the first thing I think to do with my suit is make my tiny-headed Andy Barr model recreate the Crazy Frog.

Next, I clad my housemates in them and spent a fevered evening directing them through an improvised Big Night Out. We capture every conceivable action: the wild gesticulation and discrete movements involved in small talk, big talk and smack talk; waiting to be served, patiently and impatiently; using the contactless and having it declined; getting the shots in; watching your team score and concede a last minute winner; loitering by the pool table and potting the black; rolling a cigarette and opening a packet of crisps down the middle for the table; using the urinal and observing correct Covid hygiene; every stage of inebriation, from tipsy to forcible ejection from the premises. The whole gamut, from licensed drinking hours to closing time.

I also discover that the TrueDepth camera in the iPhone X and above can be utilised for markerless facial motion capture, which, again can be recorded through iClone, into Unreal, gifting my NPC punters the ability to talk while raising virtual pints to their lips.

I’d originally intended to make it so that every single person I know, and could hope to know, would be inside, and would exclaim “here he is!” whenever my character was in their vicinity, but this turned into a mammoth task. Most of my rudimentary attempts to create the AI resulted in the characters doing nothing, except for Robbie Williams, who just followed me round the room aggressively bellowing “here he is!” to a near traumatic degree, so I bin off the AI, and elect to create a fully animated cutscene within my game.

I organise a Zoom session with my four dear friends and fellow Skehan’s devotees, Francisco, Megan, Charles and Josh (Rokoko even sent Francisco a suit) and – with the overly generous expert help of John Martin at Reallusion and professional mocap men James Martin and Joel Mack at Actor Capture – I set about animating pints across lockdown.

Now while the laptop I’d been generously lent for the task was magnitudes better than anything I own, it turns out attempting to ‘render’ out animated sequences which aren’t three-second clips of a single stationary cube – but are, in fact, of a rammed pub with an ill-advised amount of moving characters and extremely intricately modelled bar-banisters – while using a machine that hasn’t been built for the express purpose of launching satellites into space takes literal days of human life. Sacrifices had to be made with regards to lighting, textures, level of detail, frame-rate, and anything which would’ve added to the overall ‘quality’.

However, having never animated before, in only a couple of days, I manage to produce a near-ten minute long scene with fully-opposable (albeit I have to animate all the hand gestures manually, to prevent them from having Lego blocks) talking characters. This is something which – not too long ago – would’ve presumably taken a team of people who actually knew what they were doing months. Now you can do it in your room, on your own, for a laugh. Who knows, if you spend enough time on it, you might produce something even better than something which is a cross between a GTA San Andreas Rover’s Return mod and my own, specific fever dreams.

Finally, after weeks of effort and days of rendering, I’ve done it. I’ve made Skehan’s, and I’ve brought my friends inside. Despite beaming at being able to hear to their utterly depraved nonsense again, it’s still not quite right.

“I’ve seen this happen in a lot of user tests,” says Morgan. “The first thing first-time users do in VR is go right up to an NPC and get right in their grill. They violate social norms in order to quickly calibrate the level of social realism in their environment. If your NPC doesn’t react, like ‘woah, back off’, the NPC is immediately revealed to be fake.”

“Users don’t do this because they’re hell-bent on spotting the strings or ruining the trick, but because they want to know whether they are in an environment of social consequence. Is there a real person watching me? Is there the potential to be embarrassed? These questions are absolutely crucial to how we subliminally approach situations, and how seriously we take situations.”

I’m there, in Skehan’s with my nearest and dearest, but they can’t see or hear me. It’s like I’ve died and been sent to haunt them on a night out. The simulation is nearly there. It has the pub and the people, but you, the player, are absent.

The pub occupies a strange function in our society, being simultaneously multi-purpose and of no real purpose whatsoever. Birthdays? Pub. Wakes? Pub. Promoted? Pub. Made redundant? Pub. First dates, and last dates. Pub. Stressed during an exhausting stint of work, and blissfully carefree on an empty, idle weekend. Pub. In good spirits, or in the doldrums: pub. The working week and the weekend. Pub. Straight after work, and then throughout a holiday. Pub. Reunions with old friends and first encounters with new ones. The pre-lash and the night-cap. Pub. Pub on every public holiday and sporting occasion, and pub when there’s absolutely nothing on. The visit can have a justification, but just as easily none at all.

I suppose this endeavour has been about trying to create the pub of my own rose-tinted glasses, but rose-tinted glasses which – as a result of technology like the Vive – now exist, and can be worn by others, so they can see the pub the way I see it.

Many talk of the outside world melting away in the pub. Perhaps. For me, the pub is a place where – on good nights – the often-paralysing inner monologue that follows me around everywhere shuts up for a second and I clamber outside of my own head. Here, my interior melts away on contact with the outside world. I’m now blissfully present in the company of other people, in a way that seems to elude me anywhere else.

It’s possible that if my friends or I owned property with ample living space, we wouldn’t rely on the pub so much. Modern life is marked by a scarcity of space and perpetually fluctuating living circumstances. Pubs – a dying breed themselves – are among the few inexpensive places where people can still gather for no other ostensible reason or justification than wanting to be around other people. This might’ve seemed frivolous and trivial before lockdown, but now feels of incalculable value.

The speed at which the capabilities of technology are evolving is head-spinning. In a few weeks, an armchair amateur with no experience of VR, development or animation like me has been able to create something approaching a near-believable simulacra of reality. It’s ludicrously exciting to contemplate what those with more talent and time could achieve. Experiences long denied the perpetually housebound could be brought to them, allowing them to transcend physical trappings. After VR is able to convince someone they’re actually in an environment, the next step for the medium is in making them believe they’re in company, and that they’re welcome in it.

Rob Morgan sums up the value of VR (and, by extension, the pub) wonderfully: “If you can give people access to a social context they’re missing – a peaceful, social, safe environment – at a time where they’re stuck at home, I think that is a very noble endeavour.”

You probably have your own version of Skehan’s. It may not resemble Skehan’s, and it may not even serve alcohol. I miss its presence in my life, and the presence of those I idle away the evenings with, more than I can say. I would give anything to be excited by the prospect of squandering time again, precious hours stolen from the relentless obligations of existing. To walk through those front doors and be the recipient of that immortal greeting – “there he is!” – once more. To be alive!